Classification & Categorisation

Semantics (from Gr. σημαντικός (/sɪmantɪkɒs/) = meaningful ⇐ σήμα (/siːma/) = sign) is generally identified as the study of meaning in language. It can be sub-divided into approaches that allow us to study and describe the meaning(s) attributed to individual words (word-level meaning) or of larger syntactic units (multi-word or sentence-level meaning). We’ll begin our exploration into the semantics of words by looking at the former.

Basic Analysis of Word-Level Meaning

The study of word meaning is a major part of the traditional approach to semantics, whose origins can be traced back to the teachings of the Greek philosopher Aristotle. One of the main assumptions in this is that it is possible to categorise words (or concepts) according to countable and enumerable sets of necessary and sufficient features. These features, though, which modern semantics tries to identify through a technique known as componential analysis or lexical decomposition, mainly focus on the meaning of the words in isolation, something we’ve repeatedly seen can be somewhat misleading. Nevertheless, such an approach represents a useful starting point for ‘pinning down’ salient features of words, or the common core that derived or grammatically polysemous forms share, which is why we’ll explore this approach first here.

Basic Semantic Features

Basic semantic features are a means of classifying individual properties of words, i.e. capture their fundamental denotational meaning, in order to compare to, or contrasted them with, one another. Such classification systems tend to make binary distinctions, i.e. use a + to signal the presence of a feature or a - to signify its absence. Sometimes, though, it is also useful to have a third, neutral, option (indicated by 0). This then allows us to say that a feature that is relevant in one context may not be relevant in another.

- Classify the nouns in the box below according to their features, by adding selecting the appropriate feature flag (+,-, or 0) and name, and the clicking the ‘add feature’ button. Make sure you’ve placed the cursor behind the right word first.

- Think carefully about the meaning behind the feature names, and whether the options provided are always sufficient for describing all possible usages of the nouns.

- Illustrate your conclusions by citing some appropriate noun phrases.

+

While generally this kind of componential analysis is illustrated using nouns, as we’ve just done above, of course it can also be applied to other word classes. So, let’s see how we can do something similar for verb categorisation next. Obviously, though, because verbs don’t express the same things as nouns, we’ll have to find other modes of description. In order to do so, we’ll borrow and modify some concepts from Systemic Functional Grammar (SFL). This theory classifies verbs according to their process types, thereby extending the concept of transitivity we discussed briefly in conjunction with word classes earlier. There, every process type not only expresses a ‘process’ (in the widest sense, because SFL even categorises states as such), but is also characterised by the roles of the participants involved in a process. To put it in perhaps simpler terms, when we want to describe verbs, we need to say what’s going on, who’s doing what, and how the different participants involved may be affected by the process. And, in order to complete the picture, we’ll additionally consider whether we can easily add an -{ing} suffix or ED-form, and if or how their meaning changes when we do so. To describe this aspect, we’ll use the labels ‘static’ & ‘dynamic’.

- Try to understand what the labels for the different verb features in the drop-down lists below might mean.

- Use a combination of the labels in the different drop-down lists to describe the verbs listed in the box below exhaustively.

- Create an example sentence for each verb form you’re discussing.

Next, let’s try to do something similar with prepositions. As we’ve seen previously when discussing word classes, prepositions have two major features, they can indicate temporal or local relations between elements of a syntactic unit, so all we really need is a set of suitable options for describing these relations.

- For each of the prepositions below, think about which types of relations it may express, then add these to the box below.

- For each relation, check to see which types of verbs it may need to occur with in order to express the relevant relation, and provide an example sentence for each.

As we’ve seen above, any detailed way of classifying the meaning of individual words cannot really only look at the words in isolation, but depends at the very least on knowledge of the potential function(s) of its word class, as well as possibly other aspects of meaning it might take on. We’ll explore more of these aspects on the next page, but, for now, will first start looking into ways of putting words into (more or less) convenient categories that may help us to refer to similarities between them by evoking aspects of features they may share or in which they differ subtly.

Categorisation Systems & Hierarchies

In order to simplify the description of words, a highly useful starting point is to group them into classes/categories, potentially divided into a number of sub-classes. Such categories are often based on the same classes used in everyday language (folk categories), but may also be of a more technical nature (expert categories), for instance those used in biology. Each categorisation scheme generally represents a hierarchy consisting of superordinate and subordinate categories, where the subordinate elements are specific types of the superordinate class. The former are are usually referred to as hypernyms (also hyperonyms; {hyper} = above), while subordinate class elements are known as hyponyms ({hypo} = below).

The relationship between a hypernym and its individual hyponyms is usually an is-a relationship, so car and van would be hyponyms of vehicle and conversely vehicle the hypernym of car and van. This relationship between hypernyms and hyponyms is also often represented in the form of a tree that illustrates the taxonomy, as in e.g. the taxonomy of vehicles shown below

Words that appear at the same level within the hierarchy are called co-hyponyms, e.g. family car and sports car in our case.

- Try to develop a taxonomy for different types of sports.

- Justify your choices as to the different levels you may want to postulate.

Earlier on, we already looked at more traditional ways of classifying words according to certain categories, mainly based on the idea of small numbers of binary features. However, this approach does not sufficiently explain some of the decisions we may make in assigning words to specific categories. This is why we now want to look at a more modern approach, developed in cognitive linguistics – that of prototypes.

Prototypes

The idea of a prototype is originally based on the notion that objects that belong to particular class share similar features, just as we’ve seen before. In contrast to theories that just group things together hierarchically, though, prototype theory assumes that some of these features are more salient than others and help to characterise the class better. A prototype is simply the most central member of a conceptual category because it embodies all or most of these salient properties. Thus, a chair is commonly seen as a prototypical item of furniture, while something like a television or radio isn’t seen as such because, even though these two may be grouped under the category furniture, they lack some of most central features of prototypical furniture, i.e. that one can either sit or lie on them, or store something inside them. For this reason, as well as maybe that they’re not really essential for furnishing a house, they’re often regarded as more peripheral (or radial) members of the category furniture.

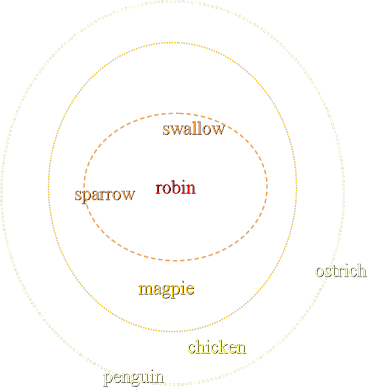

One of the other most common examples for prototypes is that of birds. In every culture, some types of birds are seen as more ‘prominent’ than others, partly maybe because they are very common or because they happen to have a more appealing appearance or song, but predominantly, shared by probably all cultures, the ideas that they have feathers, can fly, tend to sing, lay eggs, build nests, etc. Now, the more of these traits a bird exhibits, the more likely it will be seen as one of the central members of the category BIRD. Conversely, the more of these features are absent, the more the likelihood rises that we may no longer see the animal as a bird, and it thus becomes a peripheral member, as we can see in the examples listed below

- central members: swallow, sparrow, magpie, robin

- peripheral/radial members: penguin, ostrich, chicken

The following graphic provides an illustration of central vs. radial categories:

Just as with collocations, which we’ll discuss soon, the prototype may often simply be the first association that comes to mind when we think of a particular category. One of the other crucial insights in prototype theory is that there there are often no discrete features that necessarily identify all members as belonging to a category (c.f. Wittgenstein’s games).

‘Realms of Categorisation’

When we look at dictionary definitions, we essentially find the type of categorisation described above at the word level. Thus, we often encounter explanations/definitions for nouns that refer to a single entity, and following a specific structure, such as A(n) X is a type/kind of Y, where we first use the class hypernym of the noun as the basis for an initial rough categorisation, assuming that the class name already evokes most of the relevant features associated with the word. This is then generally followed by a description of some of the (more) particular features, i.e. the ones that diverge from the prototype. For verbs, similar structures are When you X, then you Y or To X is to Y.

By referring to the hypernym here, we can thus establish a background/perspective against which we to compare the concepts behinds the individual words. In terms of cognitive linguistics, this would be referred to as a base (similar to, but not to be confused with, the term used in morphology).

Words in context, on the other hand, as we’ll soon see, may have certain aspects of their meaning foregrounded, i.e. made salient, simply by occurring in these specific situational contexts. Such contexts can either be relatively static, e.g. in terminology or in-group language, where words are (nearly) always used with a specific meaning, or more dynamic, when they are used to describe (stereo)typical sequences of actions, such as ordering in a shop or a restaurant, or booking a ticket. In the first case, we can refer to the particular background of the word as a frame or domain, while, in the latter, we talk about a schema or script.

Sources & Further Reading:

Halliday, M. & Matthiessen, C. (2004). An Introduction to Functional Grammar (3nd ed.). London: Routledge.

Leech, G. (1981). Semantics: the Study of Meaning (2nd ed.). London: Penguin.

Lyons, J. (1995). Linguistic Semantics: an Introduction. Cambridge: CUP.

Taylor, J. (1995). Linguistic Categorization: Prototypes in Linguistic Theory (2nd ed.). Oxford: OUP.

Ungerer, F. & Schmid, H.-J. (2006). An Introduction to Cognitive Linguistics (2nd ed.). Harlow: Pearson Education Ltd.