As you will have seen in the previous section, intonation is a complex and difficult area, where much depends on the correct interpretation of certain patterns, an interpretation which is often made more difficult by the influence of specific segmental features, such as the absence of voicing in consonants preceding a vowel, etc. Because of this complexity, we will only be able to cover a relatively tiny part of what there is to know about the topic.

When we talk about intonation, we may actually refer to different features, depending on whether we think in terms of production, perception or systematic use as a structuring/cohesive device. On the one hand, we may mean the active modulation of the speaker’s voice – or fundamental frequency (F0) to be more exact –, caused by changing the frequency of glottal pulses in the production of voiced sounds. This is strictly on the acoustic, measurable, production side. On the other hand, we may be referring to the impression created in the hearer on the auditory side, which is usually referred to as pitch. However, the term pitch is also often, perhaps confusingly, used to refer to fundamental frequency, especially when we talk about the pitch range of a given speaker. And finally, on the third level, we may be talking about a somewhat more abstract system of F0- or pitch contours/patterns used to structure and emphasise particular bits of information. The latter may be seen as an attempt to relate the two former levels to one another, despite the fact that there are no absolutely clear physical correspondences between F0 and perceived pitch.

In order to arrive at such an abstraction in everyday speech, the listener must not only take into account segmental features influencing the pitch contour, but also the pitch range of the individual speaker and interpret each change in pitch relative to the overall range. Pitch ranges themselves, although usually different from speaker to speaker, are still to some extent physiologically conditioned, e.g. by the size of the larynx, which helps us at least to some extent to prime our expectations for a given speaker. The approximate pitch ranges and average values for men, women and children are given below:

Pitch patterns are of course also not arbitrarily long, but always extend over a certain domain. The exact extent of this domain is difficult to determine, but there are some general rules that help us to roughly determine it. We’ll discuss these in the following section.

Since units of intonation are often also units of information, it is perhaps not very surprising that they may to some extent coincide with syntactic phrases, clauses or what we generally tend to perceive as ‘sentences’. These units are often referred to as tone groups/units or intonation groups. Although their size may be rather variable and include one or more of the syntactic categories named above, there are some criteria that may help us to detect certain boundaries between them.

The most obvious boundary we may find between tone groups is a pause. Phonetically speaking, this pause is usually either a period of silence that is longer than ~60 msecs, so as to avoid confusion with the closure phases of plosives, or a filled pause, containing a hesitation marker like /əm/ or /ɜ:m/. Functionally, we can distinguish between ‘planned’ vs. unplanned pauses, where the former represents a pause that occurs at a syntactically appropriate boundary and the latter a pause that occurs in an unexpected place, such as within an NP between a determiner and the noun or adjective, e.g. in em same day on the em 17 15, or in a VP between the verb and the object, as in i wanna buy em a ticket for Edinburgh to leave em going on the ninth of October, etc. Unplanned pauses are usually either indicators of hesitation or planning strategies on the part of speaker.

When there is no detectable pause between two units, we may nevertheless perceive a break between them. This may be signalled by one of two phenomena that can be seen as two opposite sides of a coin. The first of them is final lengthening, which manifests itself as a lengthening of part of a syllable or segment, as in this audio example, where the final consonant of the word on is elongated, indicating a break before the adverbial. The counterpart to final lengthening is referred to as anacrusis by Cruttenden and represents a compression of all the syllables leading up to the first accented syllable, as in his example “I saw John yesterday / and he was just off to London”, where all the unstressed syllables in the second unit up to the stressed just would be shortened and run together, presumably by reducing and to /ən/, dropping the h of he, as well as shortening the vowel, and using a weak form of was, so that we end up with [əniwəz].

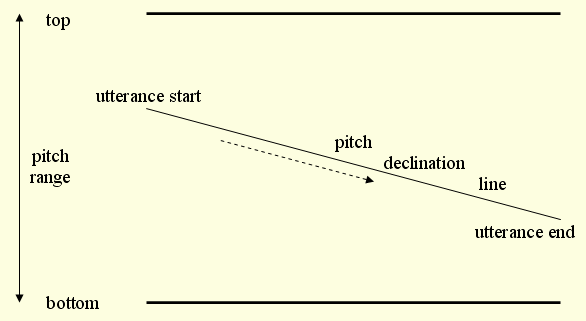

A third feature that may indicate the beginning of a new unit is a pitch reset. In order to explain this, we first need to look at one of the default assumptions about pitch in general statements, which is probably best illustrated by a simple graph.

What this illustration shows is that, within the overall pitch range, each speaker normally selects a certain sub-range, while the full range is rarely ever exploited. A new utterance/tone group is normally started with a pitch at the top of this sub-range and the pitch is assumed to decline gradually towards the end of the unit, at least for general statements in the reference accents. This effect is known as declination and the repositioning towards/at the top of the exploited sub-range is the pitch reset. Peaks or troughs in pitch outside this habitual range are normally reserved for expressions of ‘extreme’ emotions, such as excitement or boredom.

Having seen how we can potentially identify relevant boundaries, we can now proceed to look at the potential functions intonation can fulfil, and list them briefly before discussing them in a little more depth further below. As we have already seen in our discussion of stress, pitch movements (or their absence) are a very important means of providing accentuation or de-accentuation. A further important role is the signalling of different ‘sentence’ types, i.e. minimally to help us distinguish between utterances of a stating as opposed to a querying nature, although this distinction is by no means as obvious as some people make it out to be. We will certainly have to return to the issue a little further below, when we talk about some default assumptions. A third use of intonation is in the grouping of information. It helps us e.g. to indicate whether certain chunks of information belong together (e.g. lists, certain types of relative clauses) or are to be seen as asides or additional information, such as in parentheticals, relative clauses or appositions. The final, but probably most often quoted, function is ‘attitudinal’ marking. This encompasses the different ways of signalling the attitude of a particular speaker towards an interlocutor. For example boredom/routine or tiredness on the part of the speaker are usually said to be signalled by a level intonation, surprise by a rise-fall, etc.

When we read a written text, we do not arbitrarily stop at some places or run on at others. Instead, we try to give the text some structure, usually by following the punctuation inside the text or its structural layout. In a sense, though, the conventions we apply when writing a text are simply codified attempts to reflect stress & intonation in spoken language, which is still our primary means of communication. Let us now take a closer look at how the functions discussed above may be reflected in writing and, conversely, what we may do when we re-convert the written words to their spoken form.

The first of our functions discussed above, accentuation, is obviously relatively difficult to achieve in writing, unless we resort to means such as putting words into boldface, italics, small capitals, etc. However, these features are rarely exploited in conventional writing and there seem to be no conventions for de-accentuation at all, although we could of course do something like reducing the size of unimportant textual items. Because it is difficult to represent accentuation, written language has even resorted to employing special syntactic means of creating emphasis, such as the use of cleft sentences of the type It was so-and-so, who did such-and-such..

Function number four, attitudinal marking, is also something very difficult to achieve in a written text because we have very few typographical means of expressing attitude, apart from possibly using scare quotes (‘’) to signify that we want to express something other than the literal meaning of the word(s) they contain, whatever this ‘something other’ may be. When we do want to attribute certain attitudes to people speaking in a novel or a play, we have to resort to stage instructions or markers of indirect speech to express them. So, for example, we may often find expressions like: she said something in a bored/an excited tone of voice, etc., but even if these seem to express a relatively clearly defined attitude, we sometimes need to be careful in interpreting them correctly in their appropriate cultural context. Thus, if we read literary works from up to maybe the beginning of the 20th century, we may often find the expression he/she cried used in a way that will probably evoke connotations of high excitement and a certain type of voice quality that is more often than not not warranted by the context.

Functions two and three, i.e. grouping and ‘sentence type’ disambiguation, can be treated together and are more or less clearly reflected in punctuation or text structuring, although we often find a kind of multi-functionality of pitch patterns which can often only be resolved by the context, but for which we may not be able to find any absolutely clear labels, either. Here, we can first of all distinguish between the roles of punctuation in marking potential major or minor intonation(al) boundaries, indicated by || and |, respectively. Those punctuation marks that tend to signal what is commonly perceived as sentences, i.e. full stop, question mark, exclamation mark and colon, also tend to have the highest potential for producing major intonational boundaries, including longer pauses and a pitch reset. The semi-colon is similar in nature, especially when it separates relatively long sentential units from one another.

However, major boundaries can also belong to, or be associated with, other types of textual units that we may not always consider because many linguistic analyses still tend to be restricted to the level of the ‘sentence’. These specific structural units are the paragraph and one of its special sub-types, the heading. Both types of unit are clearly marked as structurally separate items in a text and thereby give the reader an even greater opportunity to signal their distinctness from the surrounding text, which is why it is even more likely for them to be marked off prosodically by pitch resets, greater empasis and longer pauses. A rather interesting fact about the heading in this context is probably that not only does it represent a special type of paragraph in the sense that it usually only consists of a single sentential unit, but also that often it does not even contain what we would consider a full grammatical sentence, but possibly only single noun phrases, which we would not expect to trigger a major tone group boundary if it occurred in context.

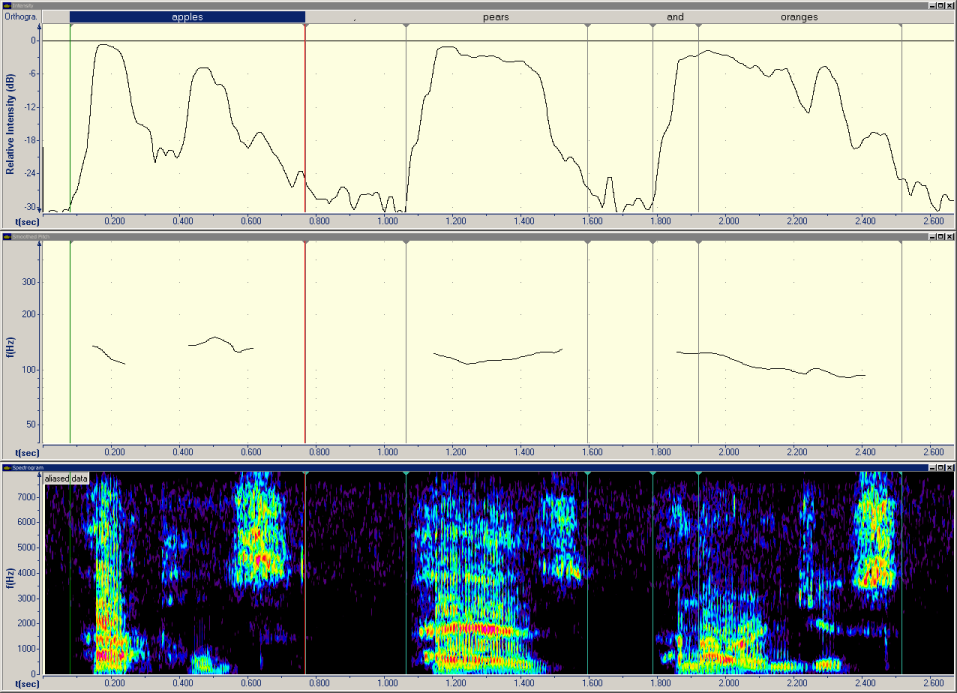

In contrast to these major punctuation marks/structures, more or less all the remaining punctuation marks tend to trigger minor boundaries. Among these, there are commata, hyphens, quotation marks and parentheses. These boundaries are usually marked by shorter pauses, final lengthening and possibly a relatively slight reset only. Out of these punctuation marks, commata are by far the most versatile in that they can serve to indicate/structure lists, appositions, relative clauses or parenthetical clauses. In lists, items belonging together are grouped by using non-final intonation patterns on all but the last item of the list, as in the following (clickable) example.

The options for the non-final intonation contours are level pitch (→), fall-rise (╲↗) or rise (↗). The pitch movement on the final element is usually assumed to be a fall, marking the end of the list, but could potentially also be a rise, if the list is part of a question that offers a choice of alternatives. Whereas commata in lists have a rather cohesive effect in grouping together the items of a list, they fulfil more or less the opposite function – i.e. one of disjunction – in appositions, (non-)defining relative clauses or other parenthetical clauses. Here, they provide an indication that we have additional information or ‘asides’, something that may strictly speaking not be absolutely necessary to convey the gist of the information. Hyphens, quotation marks and parentheses usually fulfil a similar disjunctive function, although we do not always find a minor tone group boundary following reported speech when the indirect speech marking verbum dicendi comes at the end of the reporting ‘sentence’, rather than preceding the quotation. In a similar way, a comma does not trigger an intonational boundary if it serves to delimit a vocative, as in Good morning, class/sir/madam, etc.

Other than indicating mainly major intonational boundaries, the ‘sentence indicating’ punctuation marks may obviously also serve a function that helps us distinguish between the different potential intentions we may want to express. However, just as the correspondence between perceived pitch contour and F0 is not necessarily a straightforward one, the relationship between the function of the punctuation mark and the pitch contour may vary, especially with question marks. Here, it is often somewhat naively assumed that all questions end on a rising pitch, but the situation is certainly more complex than this. We can sketch the different options for the realisation of a question mark as follows:

Imperatives – indicated by an exclamation mark – are usually expressed by a fall, as in the command Wait!. However, while this may certainly be true for imperatives uttered with some kind of ‘authority’, it may be ‘moderated’ into a slightly more tentative rising or level contour if the utterance is of a more ‘pleading’ nature, as in Wait for me!, where we may almost be able to hear a slight question mark...

Declarative sentences, indicated by a full stop, on the other hand, tend to be relatively straightforward and usually end in a fall, at least in the reference accents. In other accents, however, like a Scouse or some accents spoken mainly by younger Australian or American speakers, even declarative sentences may be realised with a rising pitch. For the latter two accents, this phenomenon is also referred to as uptalk. Use of this feature often gives an impression of tentativeness or even insecurity to many listeners.

In this section, we will try to categorise and summarise the different functions of the most common pitch contours briefly. In order to do this, it is useful to think in terms of certain default or unmarked functions of the individual contours, always bearing in mind that it is often exactly the use of pattern that deviates from our expectations that creates a certain effect in a given context.

| Contour | Meaning/Function(s) |

|---|---|

| fall | finality; authority |

| rise | unfinished; insinuating, tentative |

| level | unfinished; unresponsive |

| fall-rise | reservation (→ “..., but ...”), contrast, calling |

| rise-fall | insistence/surprise, irony |

As we have seen, a straightforward fall often creates an impression of finality. In wh-questions, this finality may possibly be in contrast with the choice in making a decision offered by uttering a yes/no-question. On the other hand, a rising or level intonation contour often indicates either non-finality or a certain kind of doubt or reservation, especially if it occurs with one of the wider contours, such as a fall-rise or rise-fall. The wider the contour, the more there seems to be a chance to express something that is extraordinary in some sense.

Cruttenden, A. (1986). Intonation. Cambridge: CUP.

Knowles, G. (1987). Patterns of Spoken English: an Introduction to English Phonetics. London: Longman.

Roach, P. (2009). English Phonetics and Phonology: a Practical Course (4th ed.). Cambridge: CUP.

Wichmann, A. (2000). Intonation in Text and Discourse: Beginnings, Middles and Ends. London: Longman.